Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics

/It’s the beginning of the year, and that means it’s time for police departments, police unions, and police critics to argue over the meaning of last year’s crime statistics. Here in New York, the debate has fallen along familiar lines—the police and the administration touting greater safety (and claiming credit for it), while scaremongers howl that the numbers are overstated, and critics complain that the arrest patterns show racial and social disparities. There is a great overview of the typical retrenchment, played out with this year’s numbers, by Al Baker and David Goodman in the Times. My thoughts, as usual, are that everyone is a little bit right and a whole lot wrong.

Statistics played a huge role in the Bloomberg-Kelly era – every year Commissioner Kelly touted a drop in crime, and critics pointed out the geometric increase in stops and frisks. From 2002 through 2006 the number of stops increased from 97,296 to 506,491. That wasn’t public at the time, of course, because the NYPD, in violation of a legal settlement, was refusing to disclose them. At the CCRB, we knew that stops were way up, because complaints of stops were way up. In the impeccable bureaucratese that I favored at the time, I wrote in our 2005 report that “complaints involving abuse of authority allegations such as ‘question and/or stop’ have risen at rates higher than complaints in which force, discourtesy, or offensive language allegations are lodged.”

One statistic we always tracked internally, once we got the stop-and-frisk numbers, was how many stop-and-frisk complaints there were in comparison to the number of stops. It was a remarkably stable number—from 2006 through 2012, the CCRB would receive, on average, one complaint for every 300 stops conducted by officers.

Criticizing stop-and-frisk (which by that time had been found unconstitutional and was already in decline) was a central prong of de Blasio’s campaign, and led to the early narrative once he took office. Without the enormously aggressive stop-and-frisk program, so the critics said, crime would immediately bounce back to 1970s levels. During de Blasio’s first week, there were more than a few articles suggesting that a crime wave was upon us. After all, there were eight murders in the first five days of 2014, two more than in the first five days of 2013—the city was “on pace” to see over five hundred murders once again. (in the end, 2014 turned out to be a record low year for murders).

This year brought the welcome spectacle of two police commissioners behaving like six-year olds in the sandbox, calling each other names and questioning each others’ success. The personal animus between Kelly and Bratton appears untethered to any policy choices. The first time they went at it, when Bratton replaced Kelly in 1994, Kelly was the advocate for community policing and Bratton wanted a tougher hand. Now they have traded roles, and you would think from their public statements that each has simply reached into the other’s press kit from twenty years ago.

For the record, the crime statistics this year are pretty straightforward, as they have been for about ten years: nothing has changed. Murders apparently went up from 333 to 350, but in a city of 8.4 million people, that means your chances of getting murdered last year increased from 0.0039643% to 0.00416667%. Higher than your chances of winning the Powerball, but still. Minor crimes are reported as going down. And here’s the thing. Of course the numbers are fake. Or at least a little fake. If you walk into a precinct and say that someone punched you in the face and took your wallet, the desk officer can say that’s a felony robbery. Or she can say that it’s a misdemeanor assault and a misdemeanor larceny. One of those helps her get a promotion, and one of them doesn’t, and you will almost certainly never be the wiser. Crime statistics are so pervasively and uniformly underreported that when the LA Times analyzed five years of data—while Bratton was commissioner—and discovered that 14,000 crimes were misclassified, the result in the New York papers was a collective yawn.

But you can only fake the statistics so much. The old saw that you can’t fake murder statistics because you can’t hide the bodies isn’t true, because whether or not a death is a “murder” as opposed to some act of negligence can’t always be determined when the person dies. (Three guesses as to whether the 333 murders in 2014 included Eric Garner, for example). Rape statistics are totally unreliable because rape is so dramatically underreported. But there are only so many tricks. Whatever you were doing five years ago, you are probably doing it now. So the statistics are probably a pretty good measure of relative crime from one year to the next, even if the top-line numbers are fudged. And over the past decade, crime decreases (or occasional increases) have been in the single-digit percentages. Crime came down twenty years ago, and stayed down. That’s really about it. That’s why when the NYPD reports its yearly statistics in historical terms, the most recent year it uses for comparison is 2001.

There is only one real story from the crime statistics last year. Ray Kelly’s stop-and-frisk program has been wholly, totally, and completely discredited as a crime fighting tool. In 2012, with the program already starting to decline, the NYPD stopped 532,911 people. By 2014 that had dropped to 45,787, and while the final 2015 numbers are not yet released, as of October they were on track to be about 25,000. That’s a 95% decrease in three years. If stop-and-frisk had had any impact on crime whatsoever, it would somehow have been reflected in the numbers (and even if you think there is some lag, we are now two years past the close of the stop-and-frisk era). Statistics really only tell stories when you see big moves. And we have seen a big move downward in stops, without any big move in crime. The case is closed: stop-and-frisk did not lower crime.

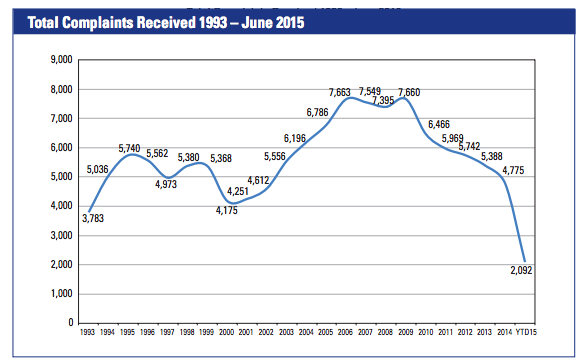

That’s the police side. But as most of you know, I am really as interested (or more) in my old shop, the CCRB. The 2015 CCRB report isn’t out yet, and I will write about it when it is. But the most appalling misstatements about criminal justice statistics this past year did not come from either police commissioner. They came from Richard Emery, the new CCRB board chair. In 2015, Emery, in an effort to show how much complaints have dropped, allowed the following chart to be printed in the CCRB’s mid-year report:

Wow what an enormous drop in complaints! - Except that all of those numbers are year-end figures, except for the last one, which covers only a six-month period. This is the sort of chart that an eighth-grade math teacher would use as an example of dishonest statistics. Emery compounded the mendacity by saying that the drop in complaints represents a “shift in the NYPD culture towards civilians." This is utter nonsense. As I said above, in most years, the CCRB would get one complaint for every 300 stops. In 2014, with stops way down and complaints kind-of-down, it received one stop and frisk complaint for every 43 stops. In relation to actual police contact with civilians, there was actually an increase in complaints to the CCRB—not surprising, given the massive attention to police conduct that has been in the media in the past few years.

From every perspective, the lesson of crime statistics this past year has been the lesson of stop and frisk. Stop and frisk has been nearly abolished while crime is steady – almost a controlled experiment showing that the program didn’t lower crime. And complaints are down almost entirely because stop and frisk is down—there is no evidence that the stops actually conducted are any different than they used to be. If you were to look at overtime abuse, PD promotions to specialized squads, and likely dozens of factors I haven’t thought of, stop and frisk would likely play a role. All of the rest of it is just noise.